🇵🇱 Goryle we mgle, czyli jak tropiliśmy te wspaniałe małpy w Ugandzie.

🇬🇧 Gorillas in the mist – how we tracked this amazing apes in Uganda.

🇵🇱 Do Ugandy pojechaliśmy przede wszystkim po to, żeby zobaczyć goryle. To jedno z trzech państw świata, w których można zobaczyć goryla górskiego na wolności. Na granicy Demokratycznej Republiki Konga, Rwandy i Ugandy znajdują się Góry Wirunga, w których na wysokości ponad 2000 m n.p.m., w parkach narodowych (Wirunga w Kongo, Wulkanów w Rwandzie oraz Mgahinga i Bwindi w Ugandzie) żyją goryle. Jeden z pierwszych odkrywców Afryki opisał je w swoim dzienniku w taki sposób: „Ludzie, którzy w większości byli kobietami, których ciała były bardzo owłosione, a nasi tłumacze nazywali je goryle”. Dziś już nie wiadomo, czy to rzeczywiście były goryle, ale tak są odtąd nazywane.

🇬🇧 We went to Uganda most of all to see the gorillas. Uganda is one of the three countries in the world where you can see the mountain gorillas in the wild. They live in Wirunga Mountains, in the national parks at over 2000 meters above the sea level, on the border of Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Uganda. In Congo it is Wirunga National Park, in Rwanda – Volcanoes National Park and in Uganda – Bwindi Impenetrable Forest and Mgahinga National Park. One of the first explorers of Africa described gorillas in is diaries this way: “People, mostly women, whose bodies were very hairy and our translators were calling them <gorillas>”. Today we don’t know if they really met gorillas, but this is how they are called since then.

🇵🇱 Nasz trekking odbył się w Mgahinga National Park. Drugim miejscem w Ugandzie, gdzie można zobaczyć goryle jest Bwindi Impenetrable Forest (Nieprzenikniony Las Bwindi – piękna nazwa, prawda?), ale ponieważ słyszeliśmy, że jest tam więcej odwiedzających, wybraliśmy inne miejsce. W Mgahinga widzieliśmy, jak ludzie dbają o goryle górskie. Może do nich dojść zaledwie jedna grupa dziennie i to złożona tylko z 8 osób. Poza tym, nie można przebywać przy małpach dłużej niż godzinę, żeby się nie zdenerwowały. Goryle są też pod stałą kontrolą i opieką. Jeżeli coś się któremuś stanie, strażnik strzela do niego z naboi usypiających, a weterynarz operuje, zaszywa rany, podaje leki itp. Następnie odstawia się takiego osobnika z powrotem do stada.

🇬🇧 For our trek we chose Mgahinga National Park. The second place where you can see the gorillas is Bwindi Impenetrable Forrest (beautiful name, isn’t it?), but we chose Mgahinga because there are less people there. We saw how the locals take care of the gorillas. You can visit the gorillas only in one group per day, not more than 8 people. And you can stay there only for one hour, not to make them nervous. The apes are also monitored and watched by the rangers. If anyone is ill they shoot it with tranquilizers so it falls asleep and then the vet can heal the wounds, give medicines and so on. Later it joins the family.

🇵🇱 Trekking rozpoczęliśmy od briefingu, na którym wyjaśniono nam wszystkie zasady. Z naszą grupą szli również dwaj uzbrojeni strażnicy. Zdziwiłem się, ale wytłumaczyli, że to dla naszej ochrony, ponieważ często szlak przekraczają dzikie słonie czy lamparty, które mogą być agresywne. Wówczas wystarczy wystrzelić w górę, żeby odeszły. Wyruszyliśmy około 8:15. Czasami trekking to nawet kilka godzin wspinania się na wysokości ponad 2000 m n.p.m. Przed nami, jeszcze w nocy, ruszyli trackersi, czyli osoby, które tropią goryle, a następnie przekazują strażnikom informacje gdzie można je znaleźć. W trakcie drogi usłyszeliśmy głos w krótkofalówce strażnika. Ten zatrzymał się i przez chwilę rozmawiał. Okazało się, że mamy wielkiego farta, bo stado goryli jest blisko, zaledwie 2-3 godziny drogi. Od tego momentu cała grupa przyspieszyła. Trzeba było przecież dojść zanim goryle się przemieszczą! Zwalnialiśmy tylko przy odchodach słoni i wydeptanych przez nich ścieżkach uważnie obserwując czy któregoś nie ma w okolicy. Po jakiś 2 godzinach strażnik stanął i podniósł głowę do góry. Patrzyłem zdziwiony co robi. Wciągnął głęboko nosem powietrze, uśmiechnął się i zapytał czy czujemy… zapach goryli – są już blisko. Spróbowałem zrobić to samo, ale szczerze to nic szczególnego nie czułem.

🇬🇧 We started the trek with the briefing when the rangers explained all the rules to us. Two armed guards also joined our group. I was a little curious but the told me that this is for our security, because the path where we would walk is often crossed by wild elephants or leopards, which can be dangerous. Then the guards fire in the air and they get scared and run away. We started the trek at around 8.15. Sometimes, it is a few hours of trek at over 2000 meters above the sea level, so it can be challenging. Before we started, still at night, the trackers who spot the gorillas went to the forest to look for them. When we were walking we heard a voice in our ranger’s walkie-talkie. He stopped and talked for a while. It turned out that we were really lucky, because the gorilla family was only 2-3 hours from us. From then on our group moved faster. We had to get there before the apes move away! We stopped only when we spotted elephant’s poo to look around and check if there are any around. After 2 hours the ranger stopped and move his head up. I watched him. He started sniffing the air, then smiled and asked us if we felt the smell of the gorillas. But we didn’t. „They are really close” – he said.

🇵🇱 Po kolejnych kilkunastu minutach marszu wreszcie je odnaleźliśmy. Najpierw zobaczyłem jedynie ciemny zarys w krzakach. Zrobiła się kompletna cisza, a prowadzący tylko dawali sobie znaki. Zwierzęta nie lubią hałasu. Musieliśmy przedostać się przez chaszcze na polanę, gdzie siedziała sobie spokojnie część goryli, w tym także silverback, czyli samiec alfa. Nazwa silverback wzięła się stąd, że ma on srebrny kolor sierści na plecach. Przyznam, że widok tego supergoryla był szokujący! Miał ze 180 cm wzrostu, prawie czarne owłosienie i ważył ze 150 kg. Podobno mogą one osiągać nawet 230 kg! Stanęliśmy jak wryci i nikt się nie ruszał. Bałem się tylko tego, że spojrzy na nas i zacznie bić się po klatce pięściami. Wiecie, to co śmiesznie wygląda w filmach i bajkach, tutaj jest bardzo niebezpieczne. Oznaczałoby to, że pokazuje nam kto tutaj rządzi, a tak robi tylko gdy się wkurzy. Na szczęście uznał, że nie stanowimy zagrożenia, usiadł i zaczął wsuwać jakieś gałązki. Po chwili pojawiło się kilka samic i dwa małe gorylki. Ależ one wszystkie miały cudne czarne oczyska!

🇬🇧 After next fifteen minutes we finally found them! In the beginning I only saw a dark figure in the bushes. We went completely silent. Only the rangers were giving signs to each other. The animals don’t like noise. We had to go through thick bushes to the clearing where the gorilla family was sitting. Among them there was a silverback – the alpha male. They are called silverback after their silver colored hair at the back. It was quite shocking! The supergorilla was 180 c tall, all black (except for the silver back) and it weighed around 150 kg. The rangers said that they can reach even 230 kg! We stopped and no-one moved. I was scared that it would start beating its chest. You know, it looks funny in the movies or cartoons, but in reality it is very dangerous. In this way they show who is the boss and that’s what they do when they feel angry or threatened. Luckily, it looked at us and decided that we were not a danger, so started biting some sticks. After a while a couple of females and two small baby gorillas came. They were so cute! And their eyes were amazing!

🇵🇱 Wiecie, że badaczka goryli Dian Fossey wcale nie poznawała goryli po figurze, kształcie twarzy czy oczach? Najważniejszą dla niej rzeczą był nos. Każdy goryl górski ma bowiem inny szlaczek skóry na nosie. One przyglądała im się, odrysowywała nosy, a potem uczyła ich na pamięć. „Rozmawiała” z gorylami naśladując je. Rzecz, której nie mogła naśladować to było uderzanie rękami o klatkę piersiową, ponieważ to było jednoznaczne z wyzwaniem goryla na pojedynek. Bić się z gorylem? Trochę słabo. W trakcie naszego trekkingu właśnie Dian Fossay była dla mnie przykładem, jak powinienem się zachowywać. Goryl na mnie patrzy? Głowa w dół, nie patrzę mu w oczy, zrywam liść i udaję, że go jem, jakbym był jednym z nich. Zachwycony kucałem i oglądałem goryle, ich sposób poruszania się, słuchałem dźwięków które wydają, patrzyłem jak bawią się z małymi i wiecie co? One są bardzo do nas podobne! Małe wariują, wieszają się na gałęziach, biegają, skaczą na młode goryle i samice – normalnie jak ludzkie dzieciaki.

🇬🇧 Do you how Dian Fossey, the scientist who studied gorillas, could tell them apart? It wasn’t their posture, face shape or eyes. The most important thing was the nose! Every gorilla has a different pattern on its nose. Dian looked at the noses, drew them and memorized them. She also tried to communicate with the gorillas mimicking their behavior. The only thing she couldn’t do was beating the chest because that would mean challenging the gorilla to fight. It wouldn’t be smart. During our trek I tried to behave like Dian Fossey. When the gorilla looked at me I looked down at the ground, started picking up some sticks or leaves and pretended to bite them, as if I was one of them. I was so amazed. I could watch them for hours – how they move, eat, play with the babies. You know what? They are like us. Especially the little ones. They were chasing each other, climbing the trees, falling down, jumping at the mothers or other juvenile gorillas. Just like small kids. The scientists say that the DNA of the gorillas is 95% same as human…

🇵🇱 Ja też miałem śmieszną przygodę z małym gorylkiem. Doszliśmy do miejsca, gdzie na środku polanki leżała sobie mama gorylica z takim maluszkiem. Karmiła go piersią. Ponieważ chciałem mieć jak najwięcej dobrych zdjęć, to w ręku trzymałem telefon i aparat, a między nogami kamerę. W pewnym momencie maluch ruszył w moją stronę. Jak to zobaczyłem, spuściłem głowę i zacząłem się wolniutko cofać. Nagle: ŁUP! Kamera uderzyła o ziemię. Gorylątko natychmiast się nią zainteresowało i przysunęło jeszcze bliżej. Był dosłownie na wyciągnięcie ręki. Zamarłem i wstrzymałem oddech. Szybka kalkulacja w głowie…. Raczej się na mnie nie rzuci. Przechyliłem się, złapałem kamerę i uklęknąłem na ziemi z głową w dół. Gorylek spojrzał na mnie i spokojnie wrócił do mamy. Było to dla mnie jedno z najbardziej niezwykłych przeżyć: cudowne i straszne. Pomyśl, co by było jakby gorylica się zdenerwowała… Zastanawiałem się dlaczego doszedł tak blisko właśnie do mnie. Rangersi powiedzieli, że zainteresował się mną, bo byłem niewiele większy od niego i pewnie chciał się pobawić…

🇬🇧 I had a funny story with the gorilla baby, too. We went to a place where there was a gorilla mum with one baby. She was breastfeeding the baby. I wanted to have many good photos, so I had a camera and a phone in my hands and a videocamera between my legs. Suddenly, the little gorilla came very close to me. I lowered my head, looked at the ground and started moving slowly back. Then: bum! My camera fell on the ground. The gorilla became very curious and moved even closer. It was at my hand’s reach. I stopped moving and held my breath. Quick thinking… it won’t probably attack me. I leaned forward, grabbed the camera and knelt on the ground with my head down. The little gorilla looked at me and moved back relaxed to its mum. It was just amazing. Wonderful and scary, too. Imagine what could happen if its mother got angry… I was wondering why it moved so close to me. The rangers told me that probably it was curious because I was only a little bigger than itself and maybe he wanted to play…

🇵🇱 Miałem wrażenie, że dopiero tam przyszliśmy, kiedy strażnik pokazał, że minęła już godzina i musimy iść. Wracając dużo myślałem o tych zwierzętach. Są tak niezwykłe, piękne, mądre i spokojne, a trzeba je chronić przed kłusownikami, którzy wierzą w jakieś przesądy, że np. dłoń goryla ma działanie lecznicze. I zabijają je… dla tej dłoni… Teraz na świecie jest tylko 1010 osobników na wolności (według badań z 2018 roku) i są one krytycznie zagrożone wyginięciem…

🇬🇧 I had a feeling that we only got there, when the ranger said that the hour is over and we have to go. On our way back I was thinking a lot about this amazing animals. They are so unique, beautiful, smart and calm. And people must protect them from the poachers who believe in some stupid superstitions that the gorilla’s hand can heal. And they kill them… to get their hands. Now there are only 1010 mountain gorillas in the wild (according to research in 2018) and they are critically endangered…

🇵🇱 Informacje praktyczne / 🇬🇧 Practical info

🇵🇱 Z trzech krajów, w których można oglądać goryle górskie, wybraliśmy Ugandę. W Rwandzie jest to dużo droższe, a w Demokratycznej Republice Konga czasami bywa niebezpiecznie.

Trekking do goryli górskich w Ugandzie można zrobić w Mgahinga (jest mniej ludzi i łatwiej zrobić zdjęcia, bo goryle mieszkają w lesie bambusowym, a nie w dżungli) albo w Bwindi Impenetrable Forest (więcej turystów, ale jest kilka rodzin goryli do wyboru i sama dżungla jest bardziej gęsta).

Zezwolenia na trekking trzeba załatwiać dużo wcześniej, co najmniej na kilka tygodni przed przyjazdem, a w sezonie nawet na kilka miesięcy.

Trekking zorganizowaliśmy przez małe lokalne biuro Encounter Africa Safaris. Naszym kontaktem był Patrick Atalyeba, który wszystko bardzo sprawnie i bez problemu nam zorganizował. Mimo, że nie braliśmy od nich wycieczki, bo podróżowaliśmy po Ugandzie sami wynajętym samochodem, to zawsze kiedy potrzebowaliśmy pomocy podczas podróży, Patrick był na nasze zawołanie.

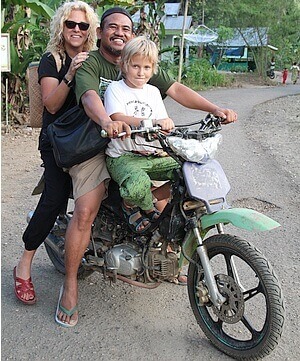

Na spotkanie z gorylami górskimi mogą chodzić dzieci dopiero powyżej 15 roku życia. Można jednak załatwić specjalne zezwolenie – skontaktujcie się z Patrickiem Atalyeba, on na pewno Wam pomoże. Ja miałem dopiero 12 lat, ale przygotowywałem reportaż dla National Geographic Kids, miałem też doświadczenie z dzikimi zwierzętami, więc władze parku narodowego wyraziły zgodę.

🇬🇧 Out of the three countries where you can see mountain gorillas, we chose Uganda. In Rwanda it is much more expensive, and in Democratic Republic Of Congo sometimes it is not so safe.

In Uganda you can trek gorillas in Mgahinga (less tourists and easier to take pictures, because the gorillas live in the bamboo forest, not in a dense jungle) or in Bwidni Impenetrable Forest (more people, but there are a couple of gorilla families to choose from and the jungle is more beautiful).

Special permits to trek the gorillas have to be arranged at least a few weeks before and in the high season even a couple of months before.

We arranged the trek with a local tour operator Encounter Africa Safaris. Our contact was Patrick Atalyeba, who arranged everything very smoothly. Although we did not buy a package tour from them (we were self-driving through Uganda) Patrick was always very helpful whenever we needed help during our trip.

Gorilla trekking with kids is theoretically possible for children over 15 years old. But you can arrange a special permit for younger kids. I was only 12 years old but I was preparing a reportage for National Geographic Kids and I had experience with wild animals so it was easier and the national park authorities gave me the permit. You can contact Patrick Atalyeba and I am sure he will help you.